English Below

À l’invitation de groupes citoyens de Baie-Comeau, dans la région de la Côte-Nord au Québec, j’ai participé comme panéliste à une rencontre publique la semaine dernière pour présenter l’état du marché mondial du gaz naturel liquéfié (GNL).

Depuis le début de l’année, la petite ville côtière de Baie-Comeau, est dans la mire d’un promoteur qui souhaite en faire la plaque tournante de l’exportation de GNL sur la côte est canadienne. Bien qu’aucun projet n’ait encore été officiellement déposé, le promoteur, la norvégienne Marinvest Energy, tient des rencontres avec des responsables politiques de haut niveau depuis plusieurs mois, dont le cabinet de Mark Carney.

C’est donc pour obtenir des réponses à des questionnements légitimes que la rencontre publique a été organisée.

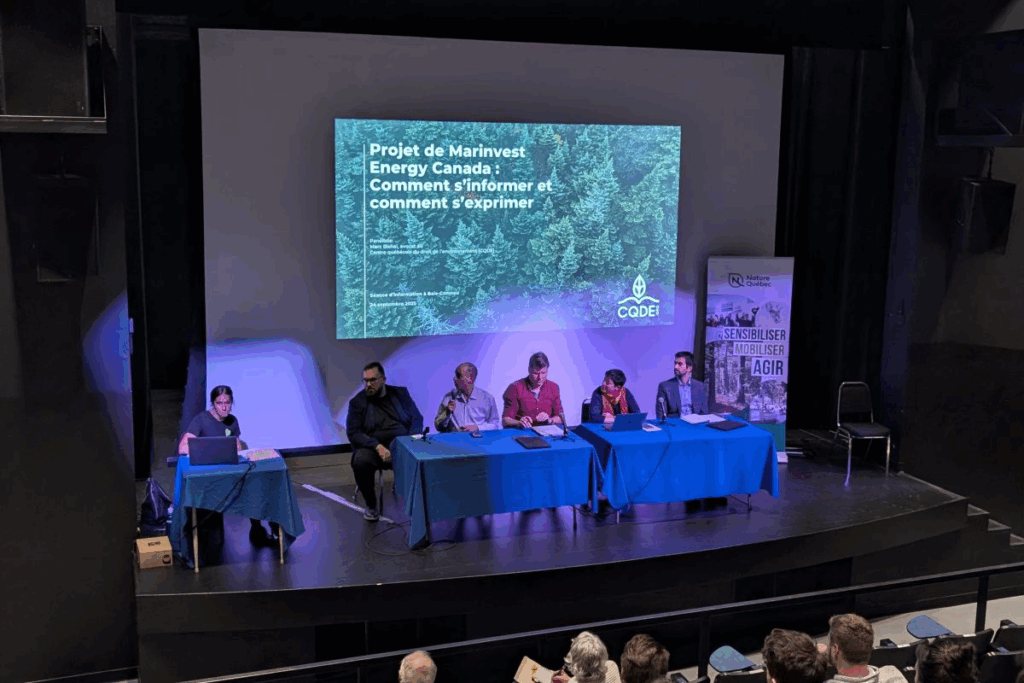

Une cinquantaine de personnes ont assisté à la rencontre publique d’information sur le projet de GNL de Marinvest Energy à Baie-Comeau. Photo: Karianne Nepton-Philippe, journal Le Manic.

Encore peu d’informations disponibles sur le projet

Nous en savons encore peu sur le projet au-delà de quelques informations qui ont filtré dans les médias, mais le projet serait essentiellement une reprise du défunt projet GNL Québec, qui comprenait la construction d’une extension du gazoduc Canadian Mainline de TransCanada de 780 km entre le nord de l’Ontario et Grande-Anse, au Saguenay. L’un des enjeux ayant mené au rejet du projet en 2021 était la protection du béluga dans le fjord du Saguenay, où un terminal d’exportation aurait augmenté le trafic maritime. En déplaçant l’usine de liquéfaction et le terminal vers le nord-est, à Baie-Comeau directement sur le fleuve Saint-Laurent, on cherche probablement à éviter cet enjeu.

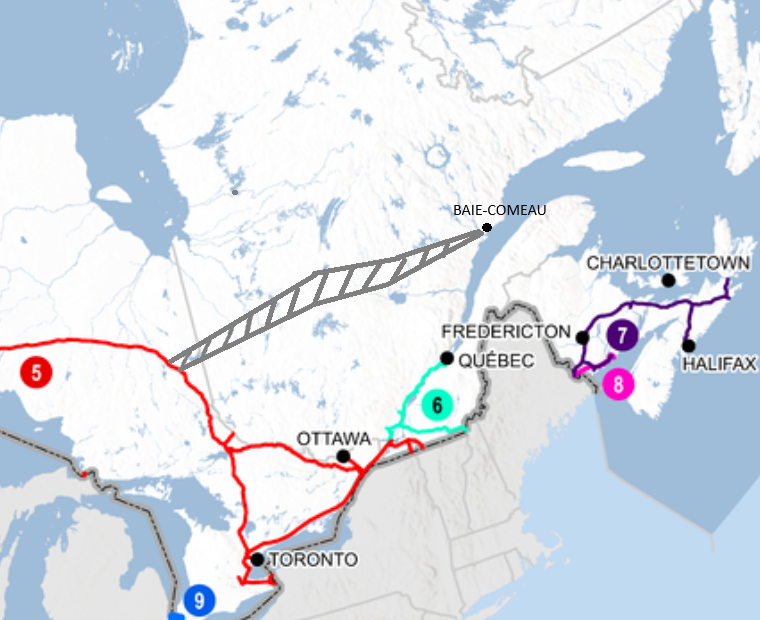

Tracé potentiel du gazoduc du projet de Marinvest Energy. Adaptation d’une carte de la Régie de l’énergie du Canada.

La longueur de la route pour se rendre à Baie-Comeau à partir du sud du Québec (10 heures pour moi) donne une impression de l’ampleur du projet de gazoduc à construire, et des investissements colossaux requis.

En 2018, GNL Québec était évalué à 13,7 milliards de dollars, soit 4,2 milliards pour le gazoduc et 9,5 milliards pour l’usine de liquéfaction et le terminal maritime. En ajustant en fonction de l’inflation, on parle de 16,9 milliards en dollars d’aujourd’hui.

Rappelons qu’il s’agissait d’une première évaluation puisque tous les projets énergétiques au Canada ont fait l’objet de dépassements de coûts importants. En tenant compte de ces surcoûts et des 250 kilomètres de pipeline additionnels, le coût du projet est estimé à 30 et 38 milliards. Une somme titanesque.

Le risque d’actifs échoués

Une voix se fait entendre pendant la période de questions: “Vu les énormes sommes engagées, y a-t-il un risque qu’une fois le projet construit, si jamais il était construit, le gouvernement se verrait en quelque sorte obligé de le maintenir en exploitation même s’il devenait moins rentable? En d’autres mots, est-ce que ça deviendrait une entreprise “too big to fail”?”

Les présentations ont été suivies d’une période d’échanges avec le public qui s’est étirée pendant une heure. Photo: Lucie Bédet, Nature Québec.

C’est en effet une préoccupation tout-à-fait valide, qui porte un nom: actif échoué. Face à une demande européenne de GNL en déclin – une baisse prévue de 26% d’ici 2030 – et une offre excédentaire à venir qui va porter les prix à la baisse, le risque est bien réel.

Les aspirations des communautés innues

Avant le panel, j’ai aussi eu la chance de rencontrer des responsables élus de la communauté innue de Pessamit, établie à 50 km à l’ouest de Baie-Comeau. Les communautés innues revendiquent des droits ancestraux sur un territoire s’étendant à l’ouest jusqu’à la Maurice et à l’est jusqu’à la Côte-Nord et au Labrador. Il ne fait nul doute que le parc éolien privé que prévoit construire Marinvest Energy pour alimenter son usine de liquéfaction aurait un impact profond sur ce territoire.

J’ai bien senti chez les élus de la communauté une volonté d’un développement selon leurs aspirations propres, et où l’obligation de consulter ne sera pas qu’une case à cocher. Le projet de parc éolien de 200 MW d’Apuiat, un partenariat à 50%-50% entre la communauté innue voisine de Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam et le promoteur Boralex, est un exemple intéressant à cet égard.

Des options pour la Côte-Nord

Toutes les régions méritent des projets économiques structurants, qui sont adaptés à la demande présente et future. Trop de projets dans les régions dites “ressources” se sont appuyés par le passé sur un modèle de développement axé sur les méga-projets, souvent prépondérants pour une région, ce qui rend les communautés vulnérables à la volatilité des prix des matières premières.

Dans la région de la Côte-Nord, des options comme l’énergie éolienne, la production d’hydrogène vert ou encore de nouvelles filières agroalimentaires s’annoncent prometteuses. Le futur dira si les vieilles habitudes ou les filières d’avenir prévaudront.

Unanswered questions after visit to potential LNG site in Baie-Comeau

Marinvest Energy’s LNG project would be located in the Baie des Anglais sector of the Port of Baie-Comeau. Photo: Renaud Gignac

At the invitation of citizen groups in Baie-Comeau, in Quebec’s North Shore region, I participated as a panelist in a town hall meeting last week to present the state of the global liquefied natural gas (LNG) market.

Since the beginning of the year, the small coastal town of Baie-Comeau. Although no project has yet been officially submitted, the developer, Norway’s Marinvest Energy, has been holding meetings with high-level politicians for several months, including Mark Carney’s office. The public meeting was therefore organized to obtain answers to legitimate questions.

About 50 people attended the public information meeting on Marinvest Energy’s LNG project in Baie-Comeau. Photo: Karianne Nepton-Philippe, Le Manic newspaper.

Still little information available on the project

We still know little about the project beyond some information that has leaked to the media, but the project would essentially be a revival of the defunct GNL Québec project, which included the construction of a 780 km extension of TransCanada’s Canadian Mainline gas pipeline between northern Ontario and Grande-Anse, in Saguenay.

One of the issues that led to the project’s rejection in 2021 was the protection of beluga whales in the Saguenay Fjord, where an export terminal would have increased maritime traffic. By moving the liquefaction plant and terminal northeast to Baie-Comeau, directly on the St. Lawrence River, the aim is likely to avoid this issue.

Potential route of the Marinvest Energy project gas pipeline. Adapted from a map by the Canada Energy Regulator.

The length of the drive to Baie-Comeau from southern Quebec (10 hours for me) gives an idea of the scale of the gas pipeline project to be built and the colossal investments required.

In 2018, GNL Québec was valued at $13.7 billion, including $4.2 billion for the gas pipeline and $9.5 billion for the liquefaction plant and marine terminal. Adjusted for inflation, that amounts to $16.9 billion in today’s dollars.

It should be noted that this was an initial estimate, as all energy projects in Canada have been subject to significant cost overruns. Taking these additional costs and the 250 kilometers of additional pipeline into account, the cost of the project is estimated at between $30 billion and $38 billion. A staggering amount.

The risk of stranded assets

A voice is heard during the question period: “Given the enormous sums involved, is there a risk that once the project is built, if it is ever built, the government will find itself somehow obliged to keep it in operation even if it becomes less profitable? In other words, would it become a ‘too big to fail’ enterprise?”

The presentations were followed by an hour-long Q&A session with the audience. Photo: Lucie Bédet, Nature Québec.

This is indeed a valid concern, which has a name: stranded assets. With European demand for LNG declining—a projected 26% drop by 2030—and an upcoming supply glut which will drive prices down, the risk is very real.

The aspirations of the Innu communities

Before the panel discussion, I also had the opportunity to meet with elected officials from the Innu community of Pessamit, located 50 km west of Baie-Comeau. The Innu communities claim ancestral rights to a territory stretching west to Maurice and east to the North Shore and Labrador. There is no doubt that the private wind farm that Marinvest Energy plans to build to power its liquefaction plant would have a profound impact on this territory.

I sensed a strong desire among the community’s elected officials to pursue development in line with their own aspirations, where the obligation to consult would not be merely a box to tick. The 200 MW Apuiat wind farm project, a 50-50 partnership between the neighboring Innu community of Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam and the developer Boralex, is an interesting example in this regard.

Options for the North Shore

All regions deserve economic development projects that are tailored to current and future demand. In the past, too many projects in so-called “resource” regions have relied on a development model focused on mega-projects, which often dominate a region, making communities vulnerable to commodity price volatility.

In the North Shore region, options such as wind energy, green hydrogen production, and new agri-food industries are showing promise. Only time will tell whether old habits or future-proof initiatives will prevail.